Debaters looking to reform federal education funding or regulations should know where federal education dollars flow now. “Federal Education Funding: Where Does the Money Go?,” (US News, January 14, 2016), provides a recent overview with helpful charts.

First US News notes that federal education spending “education has surged over the last decade and a half,” up over 36% since 2002, ” from $50 billion to $68 billion…”

Pell Grants provide college tuition for low-income students, are are “by far” the federal government’s biggest education expense: “fiscal 2016, the government is spending $22 billion to fund Pell Grants, twice what was spent in 2002.”

Next are grants for school districts with low-income students, and grants for special education, both of which have risen significantly:

known as Title I. Funding for the program also saw a big increase since 2002, going from $10.4 billion to $14.9 billion this year, an increase of 43 percent.

Special education was another big winner, with funding now at $11.9 billion – an increase of nearly 60 percent since 2002.

The US News article lists other federal K-12 programs where funding has increased significantly since 2002. And starting with 2002 is useful because the last 15 years encompasses both the Republican Bush Administration and the Democratic Obama Administration, showing bipartisan support for increased federal education spending.

The Brookings Institution, a center or center-left think tank, makes the case for federal K-12 funding reform. “Why federal spending on disadvantaged students (Title I) doesn’t work,” (November 20, 2015). The study recommends increased federal funding, but also calls for reforms to guide more research to learn what works and how to better direct funds to low-income students:

Efforts to reauthorize the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) have generated contentious debates about annual testing and accountability. Both the Senate and House versions, now headed to conference, maintain annual testing and push accountability back to the states.

Curiously missing from the debates has been the evidence of whether or not ESEA achieves its objectives.

At the college level, critics of increased federal spending argue these funds have pushed college tuition higher (more on this claim below). Also, since the “Great Recession” state funding for college education has fallen while federal funding has surged.

State funding was 65% higher than federal funding from 1987 to 2012, according to “Federal and State Funding of Higher Education,” (Pew Charitable Trusts Issue Brief, July 11, 2015) but that changed:

… this difference narrowed dramatically in recent years, particularly since the Great Recession, as state spending declined and federal investments grew sharply, largely driven by increases in the Pell Grant program, a need-based financial aid program that is the biggest component of federal higher education spending.

The study also looks at overall federal support for higher education:

Though only about 2 percent of the total federal budget, higher education programs make up a large share of federal education investments. For example, about half of the U.S. Department of Education’s budget is devoted to higher education (excluding loan programs). Higher education funding also comes from other federal agencies such as the U.S. Departments of Veterans Affairs and Health and Human Services, and the National Science Foundation.

“Impact of Pell Surge: Federal spending has overtaken state spending as the main source of public funding in higher education,” looks at the implications of increased federal spending alongside reduced state funding for higher education:

Federal and state funds have different missions. The majority of state funding is used to fund specific public institutions, whereas federal funding is generally awarded through student aid and research grants. State funding goes primarily to public institutions, while federal funding goes to students at public, private and for-profit colleges, and to researchers at public and private universities.

Critical of increased state and federal funding for higher education is economist Richard Vedder’s 2004 book, Going Broke by Degree. Vedder’s Forbes column, “Are We Still Going Broke By Degree?,” (November 1, 2016) his research:

From 1980 to 2014, by contrast, tuition fees rose sharply relative to people’s income, leading to a soaring student loan debt burden (actually, the reverse probably is more true: the availability of low interest loans induced colleges to raise tuition fees aggressively). This reflected both soaring tuition fees and a slowing of the growth in incomes, especially since 2000.

Vedder reports Census Bureau data showing that though median incomes are up significantly over the last two years, college tuitions have not risen as fast:

For two year schools, the increase was similar to four year public institutions, 1.7 percent. Yet the Census Bureau indicated that the inflation-adjusted increase in median household income in 2015 was over five percent. Income increases were accelerating, tuition hikes were declining.

Vedder then argues colleges divide into three categories he compares with cars (Mercedes/Lexus, Chevy/Toyota, and Used Cars) and looks at tuition increases and student demand for each.

See also Vedder’s “Seven Ways the Department of Education Has Made Higher Ed Worse,” (James G. Martin Center,October 28, 2015) which notes the New York Times May 22, 1979 editorial opposing federal control of education:

The idea [of the Department of Education] remains as unwise as when it was first broached in a Carter campaign promise to the National Education Association…. It has always been American policy…to deliberately avoid centralizing education in a way that requires direction and financing by a national ministry…. We believe that diversity of direction has served American education well and that it will continue to do better without a central bureaucracy, even a benign one.

New technologies have opened the door for new opportunities for getting a college education. “WHY FREE ONLINE CLASSES ARE STILL THE FUTURE OF EDUCATION,” (Wired, September 26, 2014) looks at the late, great MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses):

THE MOOC WAS The Next Big Thing—and then it was written off for dead. But for Anant Agarwal, one of the founding fathers of this online reboot of university education, it’s only just getting started. …

Online education was overhyped in the beginning:

In 2012, The New York Times hailed “the year of the MOOC,” and it seemed that not a day went by that there wasn’t a news story about how edX—and similar companies like Coursera and Udacity–were poised to radically change and democratize education. But then came the inevitable backlash. Critics pointedly accused these companies of overstating their potential.

Still, according to Wired, it may be time for MOOC 2.0:

This week, a team of researchers out of MIT, Harvard, and China’s Tsinghua University—all schools that offer MOOCs—released a study showing that students who attended a MIT physics class online learned as effectively as students who took the class in person. What’s more, the results were the same, regardless of how well the online students scored on a pre-test before taking the class.

The expansion of online education blurs the line between high school and college education. Debaters research federal K-12 programs will overlap other debaters researching federal higher education reforms. The Wired article discusses edX:

More recently, edX found yet another application for its courses: college prep. In an effort to cut their budgets, school districts across the country have cancelled advanced placement courses, even as students increasingly look to those courses as a way to cut down on college tuition costs. EdX is now hoping to fill that gap by allowing students to take those courses online.

A previous post (Informal Schools in the U.S. and Developing World) looked at many alternatives for students to earn college credit during high school years, including Tribr in India, and more in “AP, DC, DE, IB: An A–Z Guide to College Credit in High School”:

There are lots of different programs for students eager to get started with college work — Advanced Placement (AP), dual credit (DC), dual enrollment (DE), and International Baccalaureate (IB).

MIT’s OpenCourseWare website is here. Federal funding is available for online education. “Federal Student Aid for Online Learning Programs,” (Peterson’s, June 21, 2016) explains:

MIT’s OpenCourseWare website is here. Federal funding is available for online education. “Federal Student Aid for Online Learning Programs,” (Peterson’s, June 21, 2016) explains:

You can access up-to-date information about federal financial aid programs at the U.S. Department of Education’s Web site, www.studentaid.ed.gov, or by calling 1-800-4-FEDAID. You’ll see that much of what is available to non-traditional students is similar, if not identical, to the resources available to traditional students.

“FACT SHEET: Expanding College Access Through the Dual Enrollment Pell Experiment,” (U.S. Department of Education, May 16, 2016). One way to expand opportunities for low-income students is to let them escape the limitations of their school through dual-enrollment, earning college credit from home or school:

Dual enrollment, in which students enroll in postsecondary coursework while also enrolled in high school, is a promising approach to improve academic outcomes for students, particularly those from low-income backgrounds. Selected experimental sites are required to ensure Pell-eligible students are not responsible for any charges for postsecondary coursework after applying Pell Grants, public and institutional aid, and other sources of funding. About 80 percent of the sites are community colleges, and the Administration continues to place a strong emphasis on offering responsible students the opportunity to pursue an education and training at community colleges for free.

“Indiana teen is graduating college — before she gets her high school diploma,” (USA Today, May 3, 2017) reports on Raven Osborne:

Osborne, who has been taking college classes part-time, is about to graduate from college — before she gets her high school diploma.

And now she is going to be a teacher at the same high school.

Osborne, a senior at the 895-student 21st Century Charter School in Gary, will earn a bachelor’s degree in sociology with a minor in early childhood education from Purdue University Northwest on May 5, then graduate from high school on May 22.

See also this 2015 USA Today story: “More students getting college degrees in high school.”

College isn’t for everyone, and certainly not for everyone in high school or junior high, but why not allow wider choice for interested students. “College classes for middle school students? It’s happening in Hayward,” (EdSource, January 25, 2016) begins:

The students giggle, squirm and whisper to each other as their instructor gets ready to begin. It’s the start of a typical middle school class except for one thing: these 12-year-olds are taking a college course.

The program’s goal is to expose students without family experience with college education to the opportunity early:

The district wanted to use after-school time to propel students ahead, rather than focusing only on remediation or support for classroom work, Wu-Fernandez said. “We thought, ‘What better way to promote college and career readiness?’”

No easy answers for state and federal special education funding, expenditures, and priorities, but the lack of date makes the challenge harder. “

No easy answers for state and federal special education funding, expenditures, and priorities, but the lack of date makes the challenge harder. “

MIT’s OpenCourseWare website is here

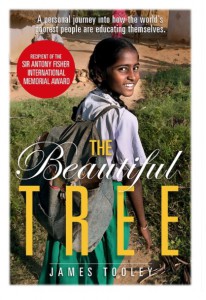

MIT’s OpenCourseWare website is here While researching private schools in India for the World Bank, and worrying that he was doing little to help the poor, Professor Tooley wandered into the slums of Hyderabad’s Old City. Shocked to find it overflowing with small, parent-funded schools, he set out to discover if they could help achieve universal education. So began the adventure lyrically told in The Beautiful Tree—the story of Tooley’s travels from the largest shanty town in Africa to the mountains of Gansu, China, and of the children, parents, teachers and entrepreneurs who taught him that the poor are not waiting for educational handouts. They are building their own schools and learning to save themselves.

While researching private schools in India for the World Bank, and worrying that he was doing little to help the poor, Professor Tooley wandered into the slums of Hyderabad’s Old City. Shocked to find it overflowing with small, parent-funded schools, he set out to discover if they could help achieve universal education. So began the adventure lyrically told in The Beautiful Tree—the story of Tooley’s travels from the largest shanty town in Africa to the mountains of Gansu, China, and of the children, parents, teachers and entrepreneurs who taught him that the poor are not waiting for educational handouts. They are building their own schools and learning to save themselves. A John Holt website

A John Holt website  Psychology Today has a series of ADHD in France articles, beginning with “

Psychology Today has a series of ADHD in France articles, beginning with “